Concepts

1. What is Social Return on Investment

SROI is a technique used for understanding, measuring, and reporting the social, economic and environmental value created by an activity (e.g., intervention, programme, policy or organisation). [1] It measures the monetised social values created by the activity in relation to the relative cost of achieving those values. [2] Many scholars recognize that SROI is based upon the principle of cost-benefit analysis, and some refer to SROI as “social CBA”. [3]

Social value has been defined as the value created by an initiative (or an organisation) with regard to the social, psychological and economic well-being of citizens, as well as environmental benefits to the society. [4]

2. What are the major functions of SROI analysis for program management?

(1) Social Value communication: a single metric that aims at summing up the social impact. [5]

(2) Resource allocation: translates social outcomes and cost into monetary values for decision making. [6]

(3) Organizational Learning: a learning process to understand where value is created, with the objective to improve performance. [7]

3. What are the major guidelines for SROI study?

Internationally, one widely used implementation model for SROI analysis is the six-stage model published by the Office of the Third Sector of the Cabinet Office of the UK government. [8] The six stages are

(1) Establishing scope and identifying key stakeholders,

(2) Mapping outcomes,

(3) Evidencing outcomes and giving them a value,

(4) Establishing Impact,

(5) Calculating the SROI, and

(6) Reporting, using and embedding.

Details of the six-stage model can be found in this report.

Some reports also highlighted the major consideration in designing and performing SROI study. For instance, the guideline published by the Office of the Third Sector of the Cabinet Office of the UK government spelt out SEVEN principles for SROI study (see p.96-98 in the report). Also, Academic Institute in the US proposed TEN guidelines for conducting SROI study (see p.120 for the guidelines).

In Hong Kong, some websites also provided materials for performing SROI study. For instance, the “Social Impact Measurement – Workbook: A step-by-step approach to devising outcome indicators” and “Introduction to Social Impact Measurement Hong Kong Context” are well-designed materials providing guidance for designing and performing SROI study in the Hong Kong context. In addition, the website of “Jockey Club MEL institute Project (see the page Outcome/Impact Indicator Bank)” and “Centre for Social Impact (see the page Download)” also provide useful materials (e.g., measurement scales for some common social outcomes) for SROI study design.

4. How to estimate the SROI for a program?

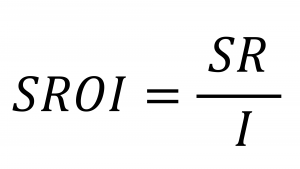

SROI calculation (a simplified form) can be expressed as follows:

Where SR refers to the amount of monetized social return of a program or service within a certain period of time, and I represents the amount of investment (e.g., funding) spent on the respective program or service within a certain period of time. In addition, the common practice in SROI estimation also involves discounting both SR and I to present value (PV). A commonly used method is to discount it by historical inflation rate within a specific territory.

In SR calculation, one key consideration is additionality. It reflects what degree the observed social return could be attributable to the intervention. [9] The rationale is that, if the outcomes would have occurred even without the presence of the intervention, it is invalid to attribute the observed social outcomes towards that particular intervention.

There are four key concepts in the consideration of the additionality issue, including deadweight, displacement and attribution, and drop-off. “A guide to Social Return on Investment” provided a succinct explanation for the concepts.

Deadweight: a measure of the amount of monetized social return that would have happened even if the activity had not taken place

Displacement: a measure of how much of the monetized social returns displaced other social outcomes.

Attribution: a measure of how much of the monetized social returns was caused by the contribution of other interventions.

Drop-off: the amount of change (e.g., decrease) in social returns of the intervention in relation to time.

In calculation, these four concepts are typically expressed in percentage.

5. How to monetize social value?

Monetizing “social outcomes” requires the practitioners to attach monetary values, also referred as “financial proxies”, to the social outcomes. In general, there are two approaches in monetizing social outcomes. [10] One is the “Social Opportunity Cost” (SOC) approach and the second is the “Willingness to pay” (WTP) approach.

The Social Opportunity Cost approach

Social Opportunity Cost is “the value to society of scarce resources that are used in connection with pursuing a particular activity” or “the value to society of the resources saved”. [11] In this monetization approach, the set of “financial proxies” used would be conceptualized as the social opportunity cost that a society would need to forego for creating the social values for the targets, or opportunity cost that a society would have saved from the social values created for the targets. “Financial proxies” used in this approach are typically budgetary or market data. [12]

Example:

|

Program |

Program objective |

Social Outcomes |

Financial proxy |

Underlying principle of the monetization |

|

A rehabilitation program |

Helping ex-offenders to re-integrate into the community |

Increased self-esteem Increased emotional well-being |

Unit cost of the program per target |

Social opportunity cost (scarce resources) that a society forego for creating the social value |

The WTP approach

For the WTP approach, financial proxy of a social outcome has been conceptualized as the average financial amount members of society would be willing to pay or receive for some particular goods and services. [13] This monetization approach arises from the concepts of “compensating surplus” and “equivalent surplus” from welfare economics, delineating the average amount a person would willingly forgo (or receive) in relation to the change of his/her welfare utility. [14]

Example:

|

Program |

Program objective |

Social Outcomes |

Financial proxy |

Underlying principle of the monetization |

|

Program to improve healthcare access |

Helping targets (e.g. older adults) to improve their health condition |

Increase in self-rated health status |

WTP of self-rated health |

Average amount individual members of a society willing to forgo in order to have an improved welfare equivalent to an improved self-rated health condition |

6. How to interpret SROI?

SROI typically presents in a ratio. For example, a ratio of 1:4 suggests that an investment of $1 yields $4 of social value. SROI larger than one (i.e., often referred to as the bottom-line) means the total amount of monetised social return of a program is greater than the total sum of its respective investment.

1. Peter Scholten, Social return on investment: A guide to SROI analysis (Amstelveen, The Netherlands: Lenthe Publishers, 2006).

2. Ross Millar and Kelly Hall, “Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement: The opportunities and barriers for social enterprises in health and social care,” Public Management Review 15, no. 6 (2013).

3. Malin Arvidson et al., “Valuing the social? The nature and controversies of measuring social return on investment (SROI),” Voluntary sector review 4, no. 1 (2013).

4. Jed Emerson, Jay Wachowicz, and Suzi Chun, “Social return on investment: Exploring aspects of value creation in the nonprofit sector,” The Box Set: Social Purpose Enterprises and Venture Philanthropy in the New Millennium 2 (2000).

5. Florentine Maier et al., “SROI as a method for evaluation research: Understanding merits and limitations,” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 26, no. 5 (2015); Arvidson et al., “Valuing the social? The nature and controversies of measuring social return on investment (SROI).”; Alex Nicholls, “‘We do good things, don’t we?’: Blended Value Accounting in social entrepreneurship,” Accounting, organizations and society 34, no. 6-7 (2009).

6. Betsy Biemann et al., “A framework for approaches to SROI analysis,” Social Edge (2005); Maier et al., “SROI as a method for evaluation research: Understanding merits and limitations.”; Patrick W Ryan and Isaac Lyne, “Social enterprise and the measurement of social value: methodological issues with the calculation and application of the social return on investment,” Education, Knowledge & Economy 2, no. 3 (2008); Joseph J Cordes, “Using cost-benefit analysis and social return on investment to evaluate the impact of social enterprise: Promises, implementation, and limitations,” Evaluation and program planning 64 (2017).

7. Millar and Hall, “Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement: The opportunities and barriers for social enterprises in health and social care.”; Ryan and Lyne, “Social enterprise and the measurement of social value: methodological issues with the calculation and application of the social return on investment.”

8. Nicholls, “‘We do good things, don’t we?’: Blended Value Accounting in social entrepreneurship.”

9. Pratik Dattani, “Challenges and misconceptions in calculating SROI,” Spotlight Public Policy, Economic and Strategy Consulting, Londonavailable at: www. economicpolicy group. com/content/uploads/downloads/2012/10/EPG-Spotlight-Public-policy-Challenges-and-misconceptions-in-calculating-SROI-v1-1. pdf (2012); Pathik Pathak and Pratik Dattani, “Social return on investment: three technical challenges,” Social Enterprise Journal (2014); Ivy So and Alina Staskevicius, “Measuring the ‘impact’in impact investing,” Harvard Business School (2015).

10. Cordes, “Using cost-benefit analysis and social return on investment to evaluate the impact of social enterprise: Promises, implementation, and limitations.”

11. Cordes, “Using cost-benefit analysis and social return on investment to evaluate the impact of social enterprise: Promises, implementation, and limitations,” 100.

12. Cordes, “Using cost-benefit analysis and social return on investment to evaluate the impact of social enterprise: Promises, implementation, and limitations.”

13. Cordes, “Using cost-benefit analysis and social return on investment to evaluate the impact of social enterprise: Promises, implementation, and limitations.”

14. Susana Ferreira and Mirko Moro, “On the use of subjective well-being data for environmental valuation,” Environmental and Resource Economics 46, no. 3 (2010).